Fred M. Locke

His First Insulators

Go to Main Page

During the winter of 1883-1884, Fred was employed as a relief telegrapher jointly by the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad Companies at Canandaigua, NY. His fiance, Mercie Peer, lived about 20 miles away at Honeoye Falls. He could not just run over to Honeoye Falls after work to see her, since that would have been a very long ride on horseback or by buggy. He probably had access to free passes to ride the train, which would have enabled him to see Mercie on his day off, after about a 1-1/2 hour train ride. The rest of the time must have been lonely for Fred during that winter, as he filled his thoughts with images of Mercie. However, his natural curiosity soon found a way to keep him busy that winter, and for the next 46 years of his life.

Most of his telegraphy work was on a very long telegraph line between Canandaigua, NY and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. When the Harrisburg telegrapher called him, Fred would open his telegraph key to break the circuit and acknowledge the call. During periods of wet and foggy weather, Fred noticed that he had difficulty keeping his telegraph instruments in adjustment. For example, when the Harrisburg operator started to call him at Canandaigua, Fred would open his telegraph key to answer but found on closing it again that Harrisburg was still calling. This puzzled him since there was only one wire, and it was grounded at each end. Since he could not receive his "OS" messages, regarding train arrivals and departures through to the Rochester train dispatcher during these outages, the Harrisburg operator would sometimes file a complaint against him. "OS" is an obsolete term meaning "On Sheet". For example, the telegrapher would respond to an incoming message by taping out a quick "OS" to let the caller know that he was ready to receive the message. The time of the call would then be recorded on a standard form (hence recorded "On Sheet") to keep track of messages. On several occasions, Fred was reported for not answering his calls by returning "OS" to the caller, and it was thought by his superiors that he was asleep at the key. Since there was no telephone at the railroad depot, the Harrisburg agent would call the local telephone operator asking for Fred, so that they could discuss the matter with him. The telephone operator would then pay a messenger ten cents to run to the depot and inform Fred that he was needed on the telephone to answer the charges of the train dispatcher.

Fred was naturally inquisitive, and these unjust accusations and messenger expenses made him determined to find the cause of the disruptions. At first, he walked down the railroad track to see if he could see something obviously wrong with the wire. Everything looked in order on the short section of line near the depot, so he quietly began an in-depth investigation of the matter to determine a possible cause for the trouble and free himself from blame. After an unexpected electrical shock from touching the telegraph key while he was mopping the floor, Fred thought that possibly the current could be leaking in a similar fashion across the glass insulators that were used to support the telegraph line. Soon he reached the conclusion that the wet glass insulators were indeed at fault. He discovered that the electrical current would easily "leak" over the surface of the wet insulators, along the surface of the pins that supported the insulators, and down the poles to the ground. If enough electrical current was allowed to leak away in this fashion, the telegraph circuit would not have sufficient current for proper operation. With most of the insulators wet from fog and rain, and each insulator allowing a small amount of electrical current to be lost to ground, then the telegraph circuit would soon be shorted out, thus breaking the signal. At last he found the cause of the problem, but how could he increase the insulation characteristics of the insulator? Finding the best solution to this problem was to consume much of his thoughts and time for the next several years.

It naturally occurred to him that the surface leakage of electricity could be greatly reduced during wet weather by increasing the surface length between the point of attachment of the wire and the crossarm. Free started experimenting in a rather novel way, using a wetted glass window pane to see what length of glass would be required to prevent the electricity from traveling across the surface. Then he experimented with various kinds of insulators tied to the main telegraph line, and a wire attached to the pinhole of the insulator. After receiving several severe shocks while moving his finger across the surface of a small insulator, he was more careful to select an insulator with a longer leakage surface between wire groove and pinhole. This lead to a new insulator design that consisted of increasing the number of petticoats and the diameter of the insulator, and lowering the distance between insulator and pin. By lowering the position of the insulator on the pin, the dripping edge of the outer skirt was brought closer to the crossarm, protecting the underside of the insulator from splashing rain. The larger insulator diameter brought the outer insulator surface farther away from the pin, allowing the addition of another petticoat to reduce electrical leakage. Both ideas helped to keep dry the recessed surface between the petticoats underneath the insulator. For further protection, the middle petticoat was later extended below the outer skirt edge to protect the inner petticoat and pin from collecting moisture.

In the November 1901 issue of the monthly trade journal, the Journal of Electricity, Power & Gas, Fred himself wrote about his experiences in the winter of 1883-1884. There he described his initial realization of the problem and one of his crude experiments:

I recall that when mopping the office floor, having wet shoes, and accidentally touching the key when operating, part of the current would ground through me. With this in view, and interposing between my finger and the key, a wetted glass plate, I was able to crudely measure the distance over which a perceptible leakage took place; applying my tongue in place of finger I could make more delicate measurements by tasting ($30.00 per month allowed me no finer instruments) and I determined that a length of about 8 inches of wet glass surface was nearly perfect insulation for 2500 volts. In possession of this data, I designed what is now known as the No. 15 [cataloged as CD 287, but the earliest style was surely CD 287.2], 4‑1/2 inch glass insulator, triple petticoat...[which] is the first recorded designed "triple petticoat" [pin-type] insulator.

After Fred and Mercie were married on March 6, 1884, she was always willing to help her husband in his pursuit of testing new ideas to improve the performance of the pins and insulators, and she even took over his telegraphy job at various times. She learned Morse Code so that she could work the telegraph key, periodically freeing Fred from his job duties, thereby giving him more time to spend on his experiments with electrical current. Shortly after Mercie began filling in for Fred at his telegrapher duties, she was given the nickname "Mertensia", because of her difficulty in correctly spelling the name of that nearby railroad station. Fred seemed always to be testing and trying new ideas, and the new Mrs. Locke encouraged him, having full faith that someday he would meet with outstanding success.

Fred's First Patent -- CD 289.9 (CD 1182)

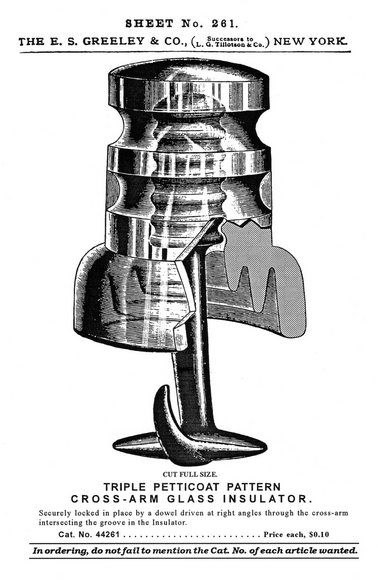

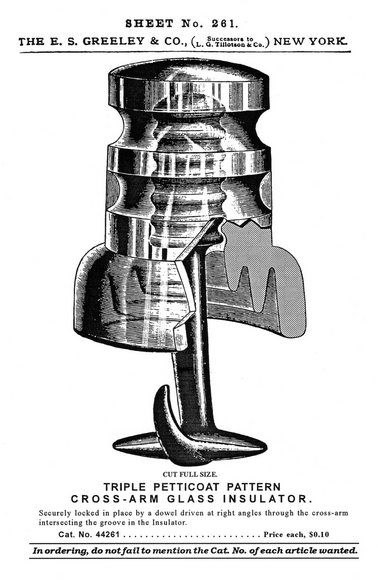

Fred was an individualist, always questioning and experimenting, never satisfied with what he knew. He was a skillful mechanic with a desire, even in his youth, for experimentation and invention. As a result of this experimentation, Fred applied for his first patent on October 8, 1888, along with John Lapp (father of John S. Lapp, founder of the Lapp Insulator Co.), covering the design of a triple petticoat, glass insulator with ram's horn hook to suspend the line wire under the crossarm. It was designed to be mounted in a hole bored in the underside of a crossarm. This non-pin-type insulator design called for an iron ram's horn hook to support the telegraph wire, which was cemented inside the glass insulator with sulfur. Patent No. 402,752 was granted to the two men on May 7, 1889. This insulator, CD 289.9, was cataloged by the E. S. Greeley & Co. Only one specimen of this glass insulator has survived, and the iron ram's horn has long since rusted away. The lone specimen has the following marking (uniquely without Fred's name) embossed around the outer skirt: "PATD. MAY 7. 89".

Why did they choose to patent a ram's horn type of insulator, instead of the more modern pin-type insulator? Perhaps the telegraph line that Fred had experimented with, between his duties on the telegraph key, also used ram's horn insulators. Mounting a ram's horn in glass and placing it underneath a crossarm was not a unique idea. The Lefferts ram's horn insulator, which also consisted of a ram's horn embedded in glass, had been used for a number of years with limited success. The major problem with the Lefferts was that insulators which had damaged glass could not be located easily, since the glass was mounted in a hole drilled in the underside of the crossarm or wooden block. The advantage of the Locke/Lapp patent was the triple petticoat feature, which allowed for a longer leakage path, and it used a larger mass of glass to guard against breakage.

CD 289.9 from the 1892 E. S. Greeley catalog. In 2006, CD 289.9 was changed to CD 1182 since it was decided not to be a pin-type insulator. The only known specimen is owned by Don Wacker of Paupack, PA. The skirt is embossed: PAT. MAY 7, 89.

(Photos of CD 1182 courtesy of John and Carol McDougald)

All evidence suggests that Fred introduced the pin-type triple petticoat insulator after CD 289.9, and sometime between 1891 and March 1893. However, Fred appears to dispute this conclusion in the November 1901 issue of the monthly trade journal, the Journal of Electricity, Power & Gas, where he continues the discussion about his No. 15 [CD 287.2 and later CD 287] triple petticoat pin-type insulator:

"Shortly afterward [after No. 15] I brought out another [triple petticoat] design, which is also illustrated [Figure 2 shown at right], and which was fitted to be received into the under side of the crossarm and fastened with wood pins or dowels, thus affording protection for the insulator."

Fred was unfamiliar with marketing insulators, so he needed a way to sell their idea. He had been the ticket agent at the Victor New York Central Railroad depot since 1888, but his income may not have allowed him to care for a wife and three children, and still have enough surplus money to invest in this new venture. Fred and John Lapp probably pooled their money in order to have the required capital to produce a few CD 289.9 insulators. They may even have convinced a friend at a local telegraph company to place a small trial order, giving them partial payment in advance. They decided to market their new insulator with the E. S. Greeley & Co. Greeley probably put them in contact with Brookfield, since they were marketing insulators through the Greeley catalog. Brookfield was undoubtedly the company who made the glass body of CD 289.9. The iron ram's horn was probably made by a local ironworks. Locke and Lapp then assembled the ram's horn in the glass insulator with sulfur cement and shipped out orders as they came in from Greeley. The 1892 E. S. Greeley catalog showed a full page illustration of CD 289.9 complete with iron ram's horn. It sold for ten cents, which was double the price of the standard pin-type glass insulator, but about one-third the cost of the Brooks ram's horn, which sold for 32 cents.

Go to Main Page